Seizures are the most common neurologic condition encountered in small animal practice, with an estimated prevalence in a referral hospital population of 1-2% in dogs and 2-3.5% in cats. Seizures are transient paroxysmal disturbances in brain function that result from an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission in the brain, and are characterized by hyperexcitability and hypersynchrony. The change in neuronal function can be identified by distinctive epileptiform activity on electroencephalography (EEG), and is typically accompanied by clinical manifestations. Clinical manifestations can be expressed as alterations in consciousness, behavioural changes, involuntary motor activity, and alterations in autonomic nervous system function such as mydriasis, salivation, vomiting, urination, and defecation.

Seizures can be preceded by a preictal phase with atypical behaviour such as restlessness, attention-seeking, or attempting to hide. The postictal phase immediately follows the seizure, during which an animal can show signs of fatigue, disorientation, restlessness, aggression, ataxia, or blindness. Postictal signs can persist from minutes to days, and the degree of postictal impairment does not necessarily correlate with the severity or duration of the seizure itself.

Classification of Seizures

Seizures are classified as either generalized or focal, based on the EEG activity present at the onset of the seizure and the clinical signs that result from the neuronal disturbance.

Generalized seizures are characterized by abnormal neuronal activity that originates from both cerebral hemispheres at the onset of the episode, and most often manifest in dogs and cats as symmetric tonic-clonic contractions of somatic muscles, loss of consciousness, and autonomic signs.

Focal seizures originate within neuronal networks in a discrete region of the cerebrum or thalamus, and can manifest as focal motor activity or behavioral signs. Focal seizures can secondarily generalize, in which case the seizure event spreads to involve both cerebral hemispheres. Focal seizures are associated with a higher incidence of underlying intracranial disease; therefore, it is important to attempt to discern the type of seizure an animal is having, as this will influence the differential diagnosis and diagnostic plan.

Diagnostic Approach for Seizures

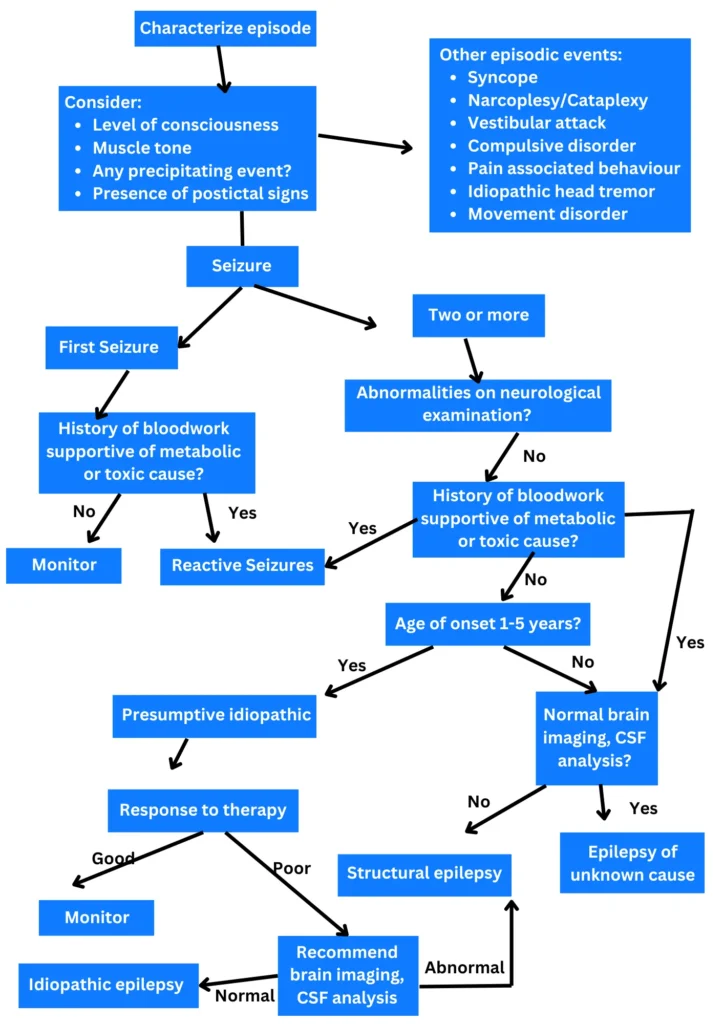

The general approach to the diagnostic evaluation of an animal with seizures is outlined in below diagram.

Historical Findings

Seizures, being episodic events, frequently are not witnessed by the veterinarian. Because of this, it is imperative that an accurate description of the episode be obtained from the pet owner to determine whether or not a seizure disorder is considered likely. Disorders that can be confused with seizures include syncope, narcolepsy/cataplexy, vestibular attacks, behavioral disorders, idiopathic head tremor and movement disorders. If the episode proves difficult to characterize based on the description alone, it can be helpful to have the owner record an episode on video for review.

A thorough history also should be obtained to explore potential causes for the seizures. The owner should be questioned regarding the age of onset, duration and frequency of seizures, whether any events tend to precipitate seizures, any past history of illness or trauma, potential exposure to toxins, vaccination history, and any family history of seizures.

Examination Findings

A general physical examination is useful in evaluating for any evidence of cardiovascular or respiratory disease, as well as any signs of systemic disease that can provide clues as to the underlying cause of seizures. In addition, a complete neurological examination should be performed to assess for any signs of forebrain disease, such as changes in mentation or behaviour, visual deficits, gait abnormalities, or postural reaction deficits.

Differential Diagnosis

Seizures often are categorized based on aetiology. Reactive seizures result from extracranial causes, in which metabolic (endogenous) or toxic (exogenous) disturbances secondarily impair normal brain function. The term epilepsy should be reserved to describe recurrent seizures due to a primary intracranial abnormality. The most common form of epilepsy in dogs is idiopathic epilepsy; this is a disorder characterized by recurrent seizures with no underlying cause other than a presumed genetic predisposition.

The analogous condition in humans is now referred to as genetic epilepsy. Idiopathic epilepsy likely is the result of a functional defect at the molecular level, and occurs more frequently in certain breeds of dogs, with a typical onset at 1 to 5 years of age. Structural or symptomatic epilepsy refers to recurrent seizures associated with a congenital or acquired structural lesion in the brain, such as hydrocephalus, encephalitis, cerebrovascular disease, or neoplasia. Epilepsy of unknown cause refers to a condition of recurrent seizures in which genetic epilepsy is determined unlikely based on age of onset or examination findings, but a structural cause is not identified. This has also been referred to as cryptogenic epilepsy or probable symptomatic epilepsy.

Classification and differential diagnosis for Seizures in dogs and cats

| Reactive seizures | Metabolic | Liver disease Renal disease Hypoglycaemia Hypocalcaemia Sodium imbalance Hyperlipoproteinemia Thiamine deficiency |

| Toxic | Heavy metals Pesticides Ethylene glycol Caffeine/methylxanthines Mycotoxins Drug | |

| Structural epilepsy | Degenerative | Neurodegenerative disorders Lysosomal storage disorders |

| Anomalous | Hydrocephalus Lissencephaly Cortical malformations | |

| Neoplastic | Primary Metastatic | |

| Infectious | Viral Bacterial Protozoal Rickettsial Fungal Parasitic | |

| Inflammatory | Granulomatous meningoencephalitis Necrotizing encephalitis | |

| Traumatic | Brain trauma | |

| Vascular | Cerebrovascular disease Hypertension | |

| Idiopathic epilepsy | Genetic | |

| Epilepsy of unknown cause | Undetermined | No structural cause identified |

Diagnostic Plan for Seizures in Dogs and Cats

As a general rule, the initial diagnostic plan for an animal with seizures should focus on potential extracranial causes. Accordingly, any animal with seizures should have a complete blood count, serum biochemistry profile, urinalysis, and serum bile acid levels measured. If intoxication seems likely based on the history, then specific tests for toxin exposure are recommended. Additional testing for systemic disease might be warranted based on examination and initial laboratory findings. Cats should be evaluated for serologic evidence of infectious disease, including feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukaemia virus, toxoplasmosis and cryptococcosis.

If extracranial causes of seizures are excluded, then intracranial disease must be explored. When considering differential diagnoses for intracranial causes, it is often helpful to take into account the likelihood of diseases based on a dog’s age at the onset of seizures. In dogs less than 1 year of age, anomalous conditions and infectious aetiologies are identified most commonly.

Ultrasound of the brain through an open fontanelle can often demonstrate the presence of ventriculomegaly in a patient with hydrocephalus. Infectious disease testing, particularly in an unvaccinated animal, might lend support for the potential diagnosis of encephalitis. However, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is necessary to exclude infectious causes, and advanced imaging of the brain is required to identify most structural abnormalities aside from hydrocephalus.

The most likely intracranial diagnosis in a dog with onset of seizures between 1 and 5 years of age is idiopathic epilepsy. Accordingly, if screening for extracranial causes produces negative results, and the signalment, history, and examination suggest that idiopathic epilepsy is likely, then further diagnostics are not necessary and a presumptive diagnosis can be made. However, if an owner desires a more definitive diagnosis, then brain imaging and CSF analysis are indicated. In addition, animals in this age group with seizures that prove refractory to treatment should undergo further diagnostic testing to evaluate for structural brain disease.

In dogs with an onset of seizures at >5 years of age, intracranial disorders such as neoplasia and cerebrovascular disease assume a greater prevalence. Serial blood pressure measurements should be performed routinely in these cases and if normal, brain imaging and possibly CSF analysis should be recommended.

Since seizures in cats are more commonly associated with an underlying cause, it is recommended that cats have advanced imaging and CSF analysis performed to evaluate for an intracranial cause for seizures, regardless of age.

Principles of Therapy for Seizures

Guidelines for Initiating Treatment

Treatment should be directed at any underlying cause identified in the diagnostic evaluation. This is particularly important if a metabolic cause is identified, as seizures secondary to disorders such as hypoglycaemia or hypocalcaemia often are refractory to antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment if the primary cause is not addressed.

A decision on whether or not to initiate AED therapy for epilepsy should take into consideration the general health of the patient, as well as the owner’s lifestyle, financial limitations and comfort with the proposed treatment plan. In general, the recommendation for initiating AED treatment based on the following criteria:

- seizure frequency of once a month or greater;

- history of cluster seizures or status epilepticus;

- seizure or postictal signs that are especially severe; and/or

- strong desire by the owner to treat the seizures regardless of the frequency or severity.

The final decision on initiating AED therapy should be made on a case-by-case basis after careful consideration of these factors.

Client education is key to the successful management of an epileptic animal. The pet owner should have a clear understanding of the goals and expectations of treatment. The owner should realize that many animals do not become seizure-free with treatment, and adverse effects are common with AED therapy, such that the goal of therapy is to maximize seizure control while minimizing adverse effects to allow for the best quality of life. Furthermore, therapy is lifelong in most instances, and it is imperative that the AED be administered on a regular basis at established treatment intervals. Finally, animals with epilepsy require continuous care, and adjustments to the treatment regimen are likely to be required over time.

In general, therapy with a single AED rather than a combination of drugs is preferred in medical seizure management, as this avoids drug-drug interactions and provides a simpler regimen that may improve compliance. A second drug should not be added until treatment failure has been demonstrated with the first drug, based on continued seizures in the face of maximum dosage or reference range serum concentrations being attained, or the presence of unacceptable adverse effects.

When choosing an AED, factors to consider include the mechanism of action, reported efficacy, potential for adverse effects and drug interactions, frequency of administration, and cost. Pharmacologic properties, dosage recommendations, and potential adverse effects for the AEDs used in dogs and cats are summarized in Table below. A more extensive discussion of treatment options for seizures can be found elsewhere.

Oral Antiepileptic Drugs Used for Treating Seizures in Dogs and Cats

| DRUG | SPECIES | RECOMMENDED STARTING DOSAGE | TIME TO STEADY-STATE CONCENTRATION (DAYS) | REPORTED ADVERSE EFFECTS |

| Phenobarbital | Dog | 2.5-3 mg/kg q 12 h | 10-14 | Sedation, ataxia Polyphagia Polyuria/polydipsia Hepatotoxicosis Bone marrow suppression Hyperexcitability |

| Cat | 1.5-2.5 mg/kg q 12 h | 16 | Sedation, ataxia Weight gain Blood dyscrasias | |

| Bromide | Dog | 30 mg/kg q 24 h | 100-200 | Sedation, ataxia Vomiting Polyuria/polydipsia Polyphagia Pancreatitis |

| Cat | Not recommended | 37 | Bronchial asthma Sedation Polydipsia Vomiting Weight gain | |

| Gabapentin | Dog | 10-20 mg/kg q 6-8 h | 1 | Sedation, ataxia |

| Cat | 5-10 mg/kg q 8-12 h | Not Reported | Sedation, ataxia | |

| Zonisamide | Dog | 5-10 mg/kg q 12 h | 3-4 | Sedation, ataxia Loss of appetite |

| Cat | 5 mg/kg q 12-24 h | 7 | Sedation, ataxia Anorexia, vomiting, diarrhoea | |

| Levetiracetam | Dog/Cat | 20 mg/kg q 8 h | 1 | Sedation, ataxia |

| Pregabalin | Dog | 3-4 mg/kg q 8 h | 1-2 | Sedation, ataxia |

| Cat | 1-2 mg/kg q 12 h | Not Reported | Sedation, ataxia |

Monitoring Response to Therapy

Epilepsy is characteristically a chronic condition, and should be managed accordingly. Ideally, the goal of therapy is seizure remission; however, fewer than half of all epileptic dogs are able to maintain a seizure-free status without experiencing adverse effects associated with medical therapy. Consequently, the primary focus of treatment is to optimize seizure control while minimizing drug-related adverse effects.

The monitoring of treatment response depends to a large extent on accurate owner observation, and owners should be instructed to maintain a calendar to record seizure activity and observed adverse effects and note any deviations in drug administration.

Therapeutic drug monitoring should routinely be performed for drugs such as phenobarbital and bromide that have a more narrow therapeutic index, and for which a reference range has been established. Drug concentrations should be measured once steady state has been achieved after initiation of treatment or dosage adjustment, when seizures persist despite an apparently adequate dosage, or when there are concerns about drug related toxicosis. In addition, drug concentrations should be measured at 6-12 month intervals to screen for any changes in drug disposition over time, and aim to maintain levels within the reference range.

Many of the newer AEDs approved for humans that are being utilized in veterinary patients, such as Zonisamide and levetiracetam, have wide therapeutic indices such that drug monitoring is not routinely recommended. Furthermore, a reference range for serum concentrations of these drugs has not been established in dogs and cats. Nonetheless, the author finds it helpful to measure trough concentrations in instances where inadequate seizure control is reported, to determine whether a dosage increase might be warranted.

What is the prognosis of Seizures in dogs and cats?

The prognosis for an animal with seizures depends on the underlying cause and response to therapy. As would be expected, animals with idiopathic disease have a better prognosis than those with structural epilepsy. Breed-related differences in seizure severity have been demonstrated among dogs with idiopathic epilepsy, with certain breeds such the Border Collie, Australian Shepherd, and German Shepherd Dog less likely to have good seizure control. Furthermore, cluster seizures and status epilepticus have been shown to negatively influence survival. However, many dogs with idiopathic epilepsy can expect a near-normal lifespan, and a small percentage of dogs (13-15%) can undergo disease remission and become seizurefree.

Pingback: Dog Walking: Essential Guide for Pet Parents - VetMD

Pingback: Chocolate Poisoning in Dogs: What You Need to Know

Pingback: CDV Disease: What You Need to Know About Canine Distemper

Pingback: Pancreatitis in Dogs and Cats: What You Need To Know

Pingback: Anaplasmosis in Dogs: Causes, Signs and Treatment

Pingback: Cane Corso Breed Info: Everything You Need to Know