This article is devoted to the causes of and clinical approach to non-physiological preputial or vaginal discharge. Here, we will not include disorders of the urological tract and/or perineal pathology, which may cause “pseudo-vaginal discharge,” such as occurs with anal sac abscess or peri-vulvar dermatitis. Physiological vaginal discharge is commonly observed in the bitch during proestrus, oestrus, pregnancy, parturition and the days to weeks following parturition. Discharge is normally seen in some cats during parturition and in the days thereafter. In male dogs, mucopurulent discharge from the prepuce without concomitant clinical signs is often considered physiological or of little consequence.

Vaginal Discharge

In order to make a proper diagnosis, one should begin with a complete history and then perform a thorough physical examination. The following information is important:

- The pet’s age

- The nature of the discharge: serosanguineous, mucoid, or mucopurulent?

- Is the animal intact or has an ovariectomy or ovariohysterectomy been previously performed? If intact, when was the last oestrus?

As the final component of the physical examination, the genital tract should be evaluated with abdominal palpation and, as indicated: digital palpation of the vaginal vault, vaginoscopy, and cytology of the vestibule to evaluate for oestrogen influence.

The more invasive examinations are usually not done or feasible in awake young animals or cats.

Additionally, any of the following may be warranted:

- Laboratory testing to assess for inflammation or bone marrow hypoplasia

- Endocrine testing of the pituitary-gonadal axis

- Ultrasonography of structures which are of concern

- Cytology of a fine needle aspirate or histologic assessment of a tissue sample.

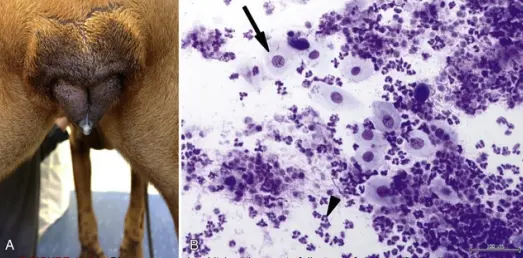

cells (arrows) and erythrocytes (arrowheads)

Serosanguineous Discharge in Intact Bitches and Queens

In young bitches during the first or second oestrous period, prolonged oestrogen influence or “split heats” are relatively common. Prolonged exposure to oestrogen can result in a persistent sanguineous discharge and can be confirmed with vaginal cytology and/or vaginoscopy.

This condition is frequently caused by failure to ovulate, as can be demonstrated by persistently low plasma progesterone concentrations. Other causes of prolonged proestrus include cystic ovarian follicles, portosystemic shunt, or exogenous oestrogen influence. In middle-aged or older dogs, the most common cause for prolonged sanguineous discharge is ovarian neoplasia. Such neoplasia can usually be visualized with abdominal ultrasonography or more advanced imaging studies.

Bloody discharge in the absence of oestrogen influence in middle-aged to older intact bitches is most frequently caused by endometritis or neoplasia of the urogenital tract. In intact bitches, vaginal tumours are often benign (e.g., leiomyoma, fibroma). Cytology or histopathology may be of value before surgical removal of the tumour(s) is attempted.

protruding into the cranial end of the tubular speculum)

Subinvolution of placental sites (SIPS) is often the cause of prolonged bloody discharge (longer than 2-3 weeks) in bitches after parturition. These bitches are otherwise healthy. The bloody discharge is usually obvious on vaginoscopy. The cells seen on vaginal smears include erythrocytes, occasional neutrophils, and vacuolated giant cells. Placental sites visualized with ultrasonography may appear large. If left untreated the discharge may continue until the next oestrus period. In queens, bloody discharge may be caused by endometritis or (partial) abortion. Rarely, bloody discharge in bitches and queens may be due to trauma, haemorrhagic diathesis or a foreign body.

erythrocytes (black arrowhead), intermediate cells (arrow) and polymorphonuclear leukocyte (green

arrowhead) and (B) a polynucleated, vacuolated giant cell (arrow)

bitch, close to the urethral orifice. This view was seen after performing episiotomy; clitoral fossa (black

arrow), possible lymphoid tissue (arrowhead), vagina (green arrow). B. Ligature after removal.

Serosanguineous Vaginal Discharge in Bitches and Queens after Ovariectomy

Serosanguineous discharge due to oestrogen influence observed in a previously ovariectomized bitch is usually caused by functional remnant ovarian tissue. The diagnosis is easily made if oestrogen influence is confirmed via vulvar swelling, vaginal cytology, vaginoscopy and/or if the plasma progesterone concentration is >2 ng/mL. If no oestrogen influence is observed and the plasma progesterone concentration is <2 ng/mL, then a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulation test or determination of anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations may be necessary to confirm a diagnosis. Determination of basal plasma luteinizing hormone (LH) concentrations, alone, is not reliable due to changes in the hypothalamic pituitary-ovarian axis after an incomplete ovariectomy.

Serosanguineous discharge after ovariectomy may also be caused by long-term administration of oestrogens, e.g., estriolum for urinary incontinence. 6 Further causes of bloody discharge after ovariectomy, without the presence of oestrogen influence, include stump endometritis due to the administration of progestins, neoplasia of the urogenital tract (more frequently malignant than in intact bitches), or uterine stump haemorrhage in the 1-2 weeks after ovariohysterectomy. Rarely, trauma, haemorrhagic diathesis or a foreign body may cause bloody discharge.

Mucopurulent Vaginal Discharge in Intact Bitches and Queens

Clear to opaque mucous vaginal discharge is sometimes observed physiologically around day 30 of normal pregnancy. Mucopurulent vaginal discharge in the intact bitch at the onset of dioestrus may be physiological as well. The most common pathological cause of mucopurulent vaginal discharge in the intact bitch after oestrus or parturition is endometritis. The vaginal discharge in association with abortion is often dark green. Additionally, vestibulitis/vaginitis may cause mucopurulent discharge. Primary vaginitis is not seen in the cat.

The aetiology of vaginitis and/or vestibulitis may be better understood by reviewing the embryologic development of this anatomic area. The area immediately proximal to the urethral opening is the caudal aspect of the internal genitalia, which fuses during development with the external genitalia. This “fusion” creates the entire vaginal vault.

Age and the stage of the oestrous cycle may be important. Infrequently, inflammation within the vestibule may be due to an infection, e.g., with canine herpesvirus. Hormonal and immunological factors may play a major role in “vaginitis/vestibulitis” in young dogs, whose clinical signs are often restricted to mucous discharge and attractiveness to male dogs.

inspection of the vulva. B. Cytology, intermediate cell (black arrow), polymorphonuclear leukocyte

(arrowhead).

Prepubertal “puppy vaginitis” and “vaginitis/vestibulitis” after the first or second oestrus are most commonly seen in large and brachycephalic breeds, sometimes as early as 3 months of age. This condition is characterized by a slightly swollen vulva, mucoid white or yellow discharge and/or attraction of male dogs. Vaginoscopy may reveal an exudate, mucosal lesions primarily in the vestibule and concomitant lymphoid follicle hyperplasia. Vaginoscopy performed when a normal bitch is in dioestrus shows a patchwork of white and red areas. Red areas in these dogs should not be mistaken for inflammation if mucosal lesions are not present.

Frequently, the signs in young dogs are self-limiting and disappear after the first oestrous cycle or after the second or third luteal phase. Treatment of “puppy vaginitis” prior to the first oestrus is not recommended for several reasons. Most drugs, such as local or parenteral antibiotics, will not alleviate signs. Application of locally active ointments or other medications are not well tolerated, especially in prepubertal bitches. Lastly, the general health and fertility of these patients is usually not affected by this condition.

“Vaginitis/vestibulitis” after the first or second oestrus may be treated by local application of ointments containing glucocorticoids. If these agents are beneficial in alleviating the signs, it would support an underlying immunological aetiology. If vaginal discharge is noted in a patient with concurrent urological problems (e.g., cystitis and/or pyelonephritis), more intensive therapy may be needed. Bacterial culture of the vagina usually demonstrates normal flora and is not a test with significant value. However, if antibiotic treatment is being considered, culture and sensitivity testing should be performed. “Vestibulitis/vaginitis” may recur, but the problem is usually self-limiting with the end of the luteal phase or with advancing age.

“Vaginitis in the mature bitch” is usually secondary to other problems such as a foreign body or neoplasia in the vagina. Very rarely, anatomic deformities may lead to accumulation of secretions or urine, leading to inflammation and vaginal discharge. Vestibulitis with discharge may also be caused by urinary incontinence, e.g., after ovariectomy. In addition, vesicles may be temporarily observed along the mucosa of the vestibule if a bitch has a canine herpes infection. Remnant ovarian tissue in a bitch, after hysterectomy, may lead to non-bloody vaginal discharge, mostly of shed superficial cells.

Mucopurulent Vaginal Discharge in Bitches and Queens after Ovariectomy

Mucopurulent discharge after ovariectomy without oestrogen influence may be caused by neoplasia in the genital tract or it may be seen in dogs with “stump endometritis” due to progesterone secretion from remnant ovarian tissue or may follow progestin administration. Progestin administration is always contraindicated after ovariectomy. If, after ovariectomy, cystic endometrial hyperplasia is present in the uterine tissue, and progestins have not been administered, then remnant ovarian tissue is present.

Preputial Discharge

Preputial discharge may be composed of fluid and cells that originate from the urinary bladder, prostate gland, testicles and epididymides, urethra, and mucosa of the penis and penile sheath. Preputial discharge may be present in either intact or castrated dogs but is extremely uncommon in tomcats. Rarely, generalized mucosal disease or haemorrhagic diathesis may cause preputial discharge.

Normal discharge in the intact male is characterized by a small amount of greyish-white to yellow mucopurulent material that may be seen at the preputial orifice as moist or dried exudate. Abnormal discharges may be mucopurulent or serosanguineous.

It is important to consider age, breed, and reproductive status of the pet. The duration and historical character of the discharge should also be noted. Systemic signs that precede or are associated with preputial discharge may accompany inflammatory conditions, infectious disease, neoplasia, trauma, or exposure to a toxin. Penile tumours are rare. The prevalence of transmissible venereal tumour varies with geographical location. A complete physical examination, including the male reproductive tract, should be performed. Digital examination and visual inspection of the preputial space (preputioscopy) may be indicated to assess the entire mucosal surface.

arrow). This tumour had also metastasized to the lungs)

In dogs and cats castrated prior to puberty, the penile tissue may appear less developed. Additionally, in cats it may be more difficult to completely extrude the penis for visualization. Based on the appearance of the preputial discharge, historical information, and physical examination findings, a list of possible diagnoses can be generated.

Further evaluation might include a complete blood count, serum biochemical profile, and urinalysis, as well as imaging of the testicles, prostate, or urinary bladder with ultrasonography. Evaluation of testicular or prostatic secretions may be possible through semen collection or prostatic massage. Additional diagnostics may include bacterial culture and sensitivity testing, fine needle aspiration, or biopsy.

Testing, as discussed, may lead to a definitive diagnosis. In the absence of definitive findings, the male should be re-evaluated at a later date. Comparison of subsequent findings with the original data may lead to a definitive diagnosis or management plan.

Pingback: Pyometra in Dogs: What You Need to Know for Early Detection